The recurring theme of diversity sparks a spirited back-and-forth at board meeting

Copyright LIHerald.com

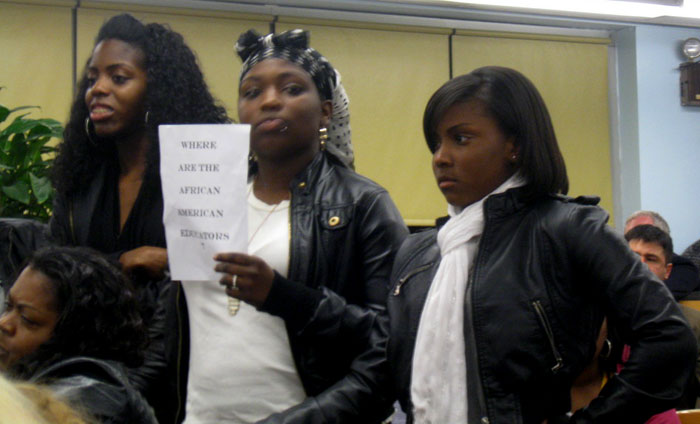

These Malverne High School students were among a dozen who attended the Malverne Board of Education meeting to ask for more culturally diverse staff.

By Lee Landor

[Note: This article and its accompanying photos and videos originally appeared on LIHerald.com on April 20, 2011. This content is the rightful property of Richner Communications, Inc.]

This article is second in a series of nine written throughout the course of a year as part of an investigative series, which won first place for best in-depth series in the New York Press Association’s 2011 Better Newspaper Contest. Read the previous and next articles.

“The only black person up there is your secretary,” said a tall woman, slapping her papers on the desk for emphasis.

The comment was directed at members of the Malverne Board of Education, who were berated at their April 12 meeting by a number of residents who claimed that cultural diversity is absent from Malverne Union Free District schools.

To an outsider, the residents’ shouting would seem out of place in what is usually a sedate setting. But to board trustees and district administrators, it’s familiar. “It’s always been a black-and-white issue,” said Trustee Danielle Hopkins, the board’s only African-American. “It’s always been a Malverne-Lakeview issue. It’s always been like this — I’ve lived here all my life.”

Hopkins, a Lakeview resident who was elected to the board in 2005, did not attend the meeting, but she wasn’t surprised to hear about what took place there. According to her and to schools Superintendent Dr. James Hunderfund, similar eruptions occur every few months, despite repeated attempts to address the issue.

“I keep hearing the same thing from when Jim Tully was superintendent in the ’70s here,” Hunderfund said. “It was the same issue, over and over, that the district doesn’t do anything or doesn’t do enough, and the truth is that everybody is doing everything we say. Nobody wants to hear it or believe it, but we are doing it.”

What these residents — primarily black residents who live in Lakeview — claim the district fails to do or doesn’t do enough is diversify its staff. Bea Bayley, president of the Lakeview NAACP, is among those who question the district’s equity in hiring.

“The fact that the district has made little to no effort to hire and retain teachers and administrators that more closely resemble the cultural demographic of the student population is troubling to most [concerned] observers of the district,” Bayley wrote in an email to the Herald. “This is extremely noticeable in the middle school, where there are no minorities in leadership positions and clearly the children are finding it hard to identify.”

But Hunderfund and Board President Dr. Patrick Coonan, along with other administrators and trustees, insist they have repeatedly explained and detailed their recruitment and hiring practices. “We have made a concerted effort to recruit minority teachers,” Coonan said after the meeting. “We’ve offered them more money, we’ve even tried to steal them from other districts.”

Diversifying district staff

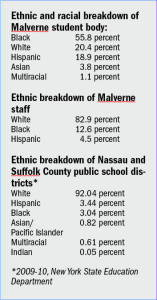

According to Hunderfund, the problem is multifarious. To start with, the pool of qualified and available minority teachers is small: Only 9 percent of qualified teaching graduates on Long Island are black. Because the Malverne district is relatively small and among the lower-paying districts in Nassau County, administrators say it is often difficult to snag quality teachers.

“It has to do with the marketplace and what people can get elsewhere,” Hunderfund said. And even when the district manages to bring in minority candidates for interviews, he added, they don’t always pan out. On several occasions, Hunderfund said, the district offered positions to minority teachers who either rejected them or accepted only to later resign to take higher-paying positions elsewhere. Residents are always encouraged to make recommendations, Hunderfund added.

At present there are 35 minority teachers and administrators in the district, comprising 17.1 percent of its certificated staff.

Copyright LIHerald.com

About three-quarters of those teachers are black. Meanwhile, more than half of the district’s students are black.

Malverne High School student body President Francina Smith, who spoke at the meeting, said those numbers don’t make sense. She was joined by about a dozen other students, some of whom held up signs that read, “I need a mentor that I identify with,” “Wanted: Diversity in my mentors” and “Where are the African American educators?”

“You’re choosing who is in our lives,” Smith, a senior, told trustees and administrators. “If we just stand around, as students, as taxpayers, as a community, and watch things occur … we’re not victims anymore — we’re participants.”

Smith and her classmates presented the board with a petition requesting that the district reconsider laying off an administrator with whom students say they have made a connection. “We need somebody we can relate to,” said senior Telia Waldo, who, without naming the administrator, described her as one of the school’s only black, female, Spanish-speaking faculty members.

“We feel she can communicate with every student,” Waldo said. “She has talked with the young women of our school and we appreciate that. It helps us out a lot. And she has motivated a lot of students — kids who never really cared about going to class now go to class because of talks with her.”

Waldo said that many students want more overall diversity, not necessarily just black or Hispanic teachers and administrators.

“I understand they need African-American teachers to relate to,” Hopkins said when asked to respond. “I fully understand that, and we do try as a board.”

According to Hunderfund, administrators understand, too, but he believes there’s more to “relatability” than race. “I don’t buy this argument that people only relate to the person who looks like [them],” he said, and then mentioned the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. “If we go back to King — let’s judge people by their character, not by the color of their skin — the truth is, it’s got to go both ways. Let’s judge our teachers by how good they teach and how well they integrate and bring children to a successful outcome, not by the fact that they’re either a certain color or dimension or come from a certain heritage.”

Coonan said the board would review the students’ petition and that no final layoff determinations had been made. He also explained that the district is bound by state law to the “last in, first out” concept, though he disagrees with it. He urged the students to contact their state representatives and speak out about the subject. “The only way to change it is by public action,” Coonan said.

The issue in context

No matter how hard the district works to diversify its staff and respond to community concerns, “people will say it’s not enough,” Hunderfund said. “I don’t know what enough is.”

At the root of the problem is the school district’s turbulent history. It was forcibly integrated in 1965, after two years of protests, demonstrations, boycotts and delays. Many outraged white parents refused to send their children to the Woodfield Road School, which had been the “colored” school. Angry black parents who lived in Lakeview boycotted the schools. Some parents opened secret schools in their homes, and others staged blockades.

Eventually the district was fully integrated, but mostly white Malverne and mostly black Lakeview were never unified. Trustee Gina Genti said, however, that it doesn’t matter that Malverne is 90 percent white or that Lakeview is 82 percent black. “We have very similar value systems,” Genti said. “We all want what’s best for the kids. The biggest difference between the two of us is the color of our skin.”

Lakeview NAACP President Bayley disagreed. “Racism still rears its ugly head at every [school board] election,” she said. “It is not the children that have the problem, but the adults who let their racist beliefs permeate the school system. Everyone needs to be honest about what is really going on in order to stop it. Too many people choose to remain silent on the issue of race, but their silence is acceptance.”

Genti said that the district has tried to work with residents who want more diversity in the schools — even inviting several of them, including Bayley, to minority recruitment seminars — but there is a fundamental disagreement that makes the issue difficult to resolve. “We’re going to be at odds about this,” she said. “I don’t think that color of the skin of anybody teaching our kids matters. They don’t see it that way.”

The problem, Genti added, “is that there’s a history in Malverne that some of the elders refuse to let go of. … And if we can’t move past our past, then we’re not going to be able to move forward.”

Attempts to address the issue by way of dialogue among administrators, board members and Lakeview residents seem to have accomplished little thus far. “After a while, you get beaten to death on this,” Hunderfund said. Still, he added, he has not given up hope that continued discussions will generate some change. “I’m up for dialogue anytime, any place with anybody,” he said. “There might be a mechanism down the road that we can [use to] get more trust and understanding. Right now, I believe … that sometimes people put up a wall and don’t want to deal with the facts.”

Hopkins said she would discuss with her fellow trustees the possibility of holding some sort of community forum in the coming months focusing on the issue. Instead of coming up at a board meeting every few months, she said, it needs to be discussed openly and frankly.

“We’re looking at 2011-2012 [and] we’re still in the same place that we were years ago, which is kind of sad,” Hopkins said. “We need to move on and be more about educating our kids and getting them into college. Black or white, purple, green, if you’re going to educate the child, it should be about the child, not always about the skin color.”

Read the previous article in the series: ‘Lakeview in need of a few good men’

Read the next article in the series: ‘Race to the top’