Copyright Associated Press

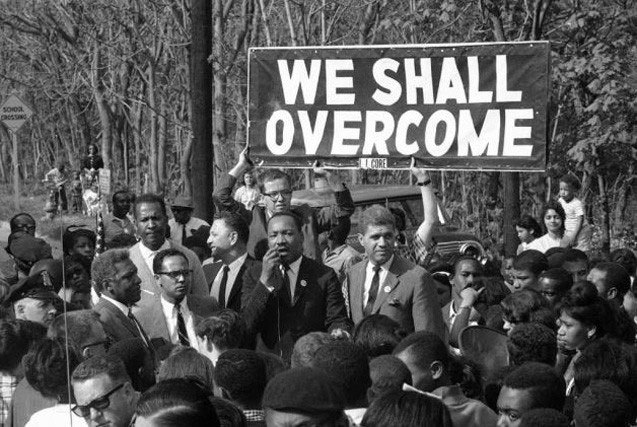

Hundreds of Lakeview residents came out to listen to the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who visited the hamlet on May 12, 1965, to show his support for the state’s integration efforts.

By Lee Landor

Note: This article and its accompanying photos and videos originally appeared on LIHerald.com on August 31, 2011. This content is the rightful property of Richner Communications, Inc.]

This article is fifth in a series of nine written throughout the course of a year as part of an investigative series, which won first place for best in-depth series in the New York Press Association’s 2011 Better Newspaper Contest. Read the previous and next articles.

By the time he was a senior at Malverne High School in 1969, DeSilva joined fellow students — black and white — to protest unfair practices in the district, which had been forcibly integrated in 1965, two years after the Supreme Court handed down an integration order. The district was integrated, but it was not unified. According to DeSilva, black students were not allowed to participate in school plays and other activities, and some white teachers were prejudiced. Several guidance counselors had advised black students like DeSilva, who had excelled in his studies, to enlist in the military instead of enrolling in college.

Eventually, he joined 136 other students for a sit-in in the lobby of Malverne High School. All of the participants were arrested for trespassing. Seeing the turmoil in a district with a growing black student population, some Malverne parents began demanding that a separate high school be built for black students in Lakeview, according to DeSilva. Others, he noted, pulled their children out of the district schools.

Opening another school is ‘ridiculous’

Having experienced that history firsthand, DeSilva was shaken to the core when he read in the Herald about a proposal to open a charter school in Lakeview (“New view from across the Ocean,” Aug. 25-31). “It’s like I’m reading something from 50 years ago,” he said. “Trying to have another school in Lakeview, separate from Malverne [schools] is ridiculous. … You’re not going to get anything from this. It was proposed back then — a separate school in Lakeview — and it was shot down.”

Malvernites Jodi and Matt Morello last month proposed opening a charter school in Lakeview, their primary motivation being to give district students an alternative. The Morellos assert that bureaucracy is destroying the Malverne school district, which they claim pushes students through without properly preparing them for college or the working world. Low state exam scores and complaints from district residents about the quality of the schools prompted them to make the proposal, they said.

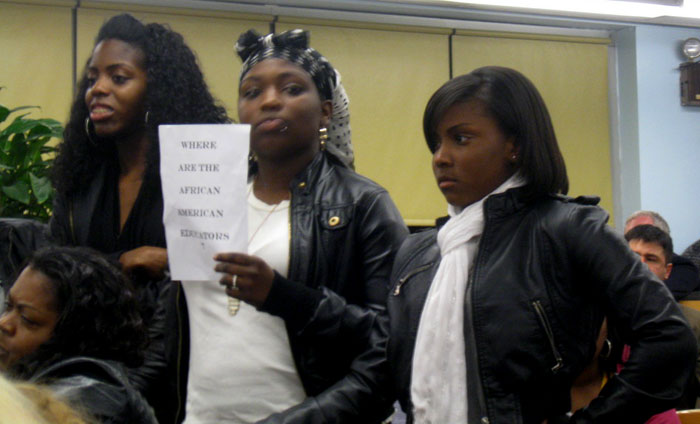

Despite the Morellos’ stated reasons, some residents questioned their motives and took offense at their suggestion to open the school in Lakeview, as opposed to Malverne. A handful of those residents took to Facebook to air complaints, and others commented on the Herald’s website.

Jeanne D’Esposito said she thinks the Morellos are “mostly interested in giving themselves a job.” Asked why she thought so, D’Esposito said, “Because I’m cynical. Because they have no other dog in this fight. Because in their interview they distort things that are occurring in this district and many, many others as a result of the bad economy, and try to turn it into a singular failing of our district.”

Yanking students out of the Malverne school district and taking hundreds of thousands of dollars along with them will do nothing for the community as whole, D’Esposito added.

In response to her comments, the Morellos said that their motive is simple: to see that education is improved. “This is not, and will never be, as some accuse, an act of ‘taking away,’” they wrote in an email to the Herald. “This is a sincere attempt to give back and we are saddened to see our good intentions questioned.”

They went on to say that they are already gainfully employed, and that opening the school would actually be a risk for them. “To suggest avarice (in the face of such risk) is illogical,” they wrote, noting that opening the school is an opportunity to create jobs where there were none — “no easy feat in this economic morass.”

A touchy subject

Although he admitted to knowing little about the problems in the school district, DeSilva said his issue was primarily with the idea that a charter school would resegregate the district and undo all of the progress made thus far. “You have to understand, this is really touchy for me,” he said. “This has gone on and on and on, and then you have a couple wanting to do exactly what the Supreme Court turned down in the ’60s — segregating Malverne, putting black students in one area. You’re not going to have white students coming into Lakeview to go to a charter school. … We all know that. So this is going to be an all-black school.”

To be clear, DeSilva said, he is not divisive and has no problems with Malverne residents. “I love everybody in Malverne,” he said. “I’m just talking about the school system.” To make his point, he cited the school incident in June, when a black student was named salutatorian instead of valedictorian, despite having a higher grade point average than the white student who was named valedictorian. The situation became racially charged shortly after the district decided to name both students co-valedictorians, and eventually forced administrators to name the black student, Aalique Grahame, valedictorian, and his white classmate, Sarah St. John, salutatorian.

Additionally, DeSilva said, the Morellos cite low test scores and other educational inadequacies as reasons for their proposal, when in fact those are widespread problems that result from the state of the economy, financial issues and, perhaps, an administration that is lacking. “You try and improve the school district,” DeSilva said. “You don’t try and segregate a portion of the school and leave them in Lakeview. This has been the cry since the ’50s to keep the students in Lakeview over here. This is another veiled attempt to do it.”

The Morellos denied DeSilva’s accusation, calling it “polemical political posturing at its worst and a complete misunderstanding of our objectives.” They reiterated their goal: to provide neighborhood children a choice where teachers have more dominion over the learning process than administrators. “Suggesting that the ugly specter of segregation is part of our secret hand of cards not only wrongly imputes us, but reveals how low on the fantasy scale of perceived racial tension the opposition is willing to sink to,” the Morellos wrote. “It is one thing to express doubts about a new charter school. It is however, a suspicious other to cast aspersions as a first response.”

That first response, DeSilva said, is a result of his passion, which comes from having lived through the civil rights movement. He remembered standing at the corner of Pinebrook Avenue and Woodfield Road on May 12, 1965, when the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. passed by in his car, waving to residents. He remembered the motivational and heartfelt speech King gave later that day before a large crowd, and the warm handshake he shared with the inspirational leader. “It was just unbelievable,” DeSilva said. “Woodfield Road was full of people.”

Taking up a fight

Although he claims to be “just a regular guy” and not an activist of any kind, DeSilva said that the matter is close to his heart, and he simply could not stay silent after reading about the charter school proposal. “I feel like my father, who died in 2006 — that I’m taking up a fight that he spent so much time doing when we first moved out here,” he said.

The Morellos feel as if they, too, are taking up a fight — for the children and members of the Lakeview and Malverne communities who have a history of criticizing the educational and staffing practices of the school district. They doubt the district will improve itself, as its superintendent, Dr. James Hunderfund, and others have suggested.

“Malverne has maintained it is good enough, so why admit the need to improve if their methods have not already let this community down?” the Morellos wrote. “And how, precisely, will Malverne schools improve? Their ostensible supporters offer no rabbit and no hat, merely a scoff that ‘a charter school won’t help.’ This is presumptuous and erroneous. A charter school will help to fill the gaps irrevocably left open by the limits of a two-school community.”

The Morellos discussed the matter with community residents on Aug. 30 at an open forum on the proposed charter school. Check the Herald next week for an update on the forum.

Read the previous article in the series: ‘View from across the Ocean’

Read the next article in the series: ‘Forum furor’